All of you!

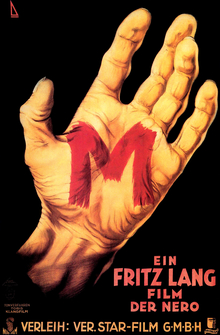

Those are the final words of Fritz Lang's movie M. If you have not seen this movie, you should. It is the only DVD I have ever seen that made me want to watch it again, with the commentary track on, right after I had finished it the first time. If you haven't seen it, please do. And then e-mail me so we can talk about it, because it's that kind of film.

not seen this movie, you should. It is the only DVD I have ever seen that made me want to watch it again, with the commentary track on, right after I had finished it the first time. If you haven't seen it, please do. And then e-mail me so we can talk about it, because it's that kind of film.

Peter Lorre plays a Hans Beckert, a pedophile whose crimes paralyze the city police and the criminal organizations of the underworld. Scenes from the meetings of city fathers and meetings of the godfathers are interspliced to emphasize the parallels between the motivations of politicians and crime bosses. Eventually, the police and the mob close in on murderer, both intent on dealing with him in their own ways.

The commentary on the Netflix DVD, by Anton Kaes of the UC Berkeley and Eric Rentschler of Harvard, contained some interesting information about Lang's somewhat clouded relationship to the Nazi party, and the debate in Weimar Germany over the death penalty. But their--well, mostly Rentschler's--references to the "social causes" of Beckert's psychopathy seemed like a stretch. The film has been restored to somthig like it's original form--it was first released in 1931 as 117 minutes long, but parts of the original have been lost, and so the restored DVD version reaches 109 minutes only through the use of several unidentified minutes of period stock footage. But there is nothing that I saw to support Rentschler's claim that Beckert's crimes are motivated by trauma suffered during WWI. Sure, it's a nice thesis, considering the situation in Germany ca. 1931, but I just don't see it in the film.

What I do see is a director uncertain about where his own morals lead him in the issues raised by the film. The final scenes, contrasting a court of criminals (most nearly a jury of Beckart's peers), with the unheard decision of a court of law, makes the viewer the final court of appeal. How can justice best be served in such a situation? The way Lang frames it, there is satisfaction in both the rule of the mob, and the higher sentiments of law-bound justice.

The final words are delivered by the weeping mother of one of Beckert's child victims. They emphasize the responsibility of the viewer not only for Beckert's fate, but also for how are decision will affect the future. The film left me wondering which side to take. To condemn the man conclusively fingered as guilty by (literally) blind justice seemed most immediately satisfying. But would such a condemnation merely perpetuate the same desire for irrational gratification that lead Beckert to commit his crimes in the first place?

not seen this movie, you should. It is the only DVD I have ever seen that made me want to watch it again, with the commentary track on, right after I had finished it the first time. If you haven't seen it, please do. And then e-mail me so we can talk about it, because it's that kind of film.

not seen this movie, you should. It is the only DVD I have ever seen that made me want to watch it again, with the commentary track on, right after I had finished it the first time. If you haven't seen it, please do. And then e-mail me so we can talk about it, because it's that kind of film.Peter Lorre plays a Hans Beckert, a pedophile whose crimes paralyze the city police and the criminal organizations of the underworld. Scenes from the meetings of city fathers and meetings of the godfathers are interspliced to emphasize the parallels between the motivations of politicians and crime bosses. Eventually, the police and the mob close in on murderer, both intent on dealing with him in their own ways.

The commentary on the Netflix DVD, by Anton Kaes of the UC Berkeley and Eric Rentschler of Harvard, contained some interesting information about Lang's somewhat clouded relationship to the Nazi party, and the debate in Weimar Germany over the death penalty. But their--well, mostly Rentschler's--references to the "social causes" of Beckert's psychopathy seemed like a stretch. The film has been restored to somthig like it's original form--it was first released in 1931 as 117 minutes long, but parts of the original have been lost, and so the restored DVD version reaches 109 minutes only through the use of several unidentified minutes of period stock footage. But there is nothing that I saw to support Rentschler's claim that Beckert's crimes are motivated by trauma suffered during WWI. Sure, it's a nice thesis, considering the situation in Germany ca. 1931, but I just don't see it in the film.

What I do see is a director uncertain about where his own morals lead him in the issues raised by the film. The final scenes, contrasting a court of criminals (most nearly a jury of Beckart's peers), with the unheard decision of a court of law, makes the viewer the final court of appeal. How can justice best be served in such a situation? The way Lang frames it, there is satisfaction in both the rule of the mob, and the higher sentiments of law-bound justice.

The final words are delivered by the weeping mother of one of Beckert's child victims. They emphasize the responsibility of the viewer not only for Beckert's fate, but also for how are decision will affect the future. The film left me wondering which side to take. To condemn the man conclusively fingered as guilty by (literally) blind justice seemed most immediately satisfying. But would such a condemnation merely perpetuate the same desire for irrational gratification that lead Beckert to commit his crimes in the first place?